A lot of things fascinate me. Evolution is for sure one. The biological process itself is marvelous enough, but I’m more interested in how selective pressures our ancestors faced affect our psychology, instincts, behaviors, how we move in the world and interact with each other today. So, I frequently consume podcasts, blogs, and books about evolutionary psychology and anthropology. One of the names I recently came across is Elizabeth Pillsworth. She’s a professor of evolutionary anthropology at California State University Fullerton. During her Ph.D. at the University of California Los Angeles, she studied human sexual strategies and mating behavior from an evolutionary perspective. Research by Pillsworth and others helps us understand our desires and behaviors that often seem ambiguous.

The dual-mating theory

I am no parent, but I can see that raising a child is one hell of a work. If you think of the wild environment in which ancestral women were raising their children, it is even tougher. They had to ensure that their kids were cared for properly in the face of ample danger. That is how coupling behavior evolved. Parents don’t usually just abandon their children and go off with other people to produce more offspring. They form pairs and take care of their offspring, increasing the chances that the carrier of their genes reaches adulthood and has kids of their own. The genes are successfully passed through generations. Mission accomplished. Well, not exactly. Coupling is definitely a great strategy. One that is still prevalent today. However, some researchers think that another strategy has evolved alongside it: dual mating.

Dual mating theory suggests that women tend to form a long-term bond with one partner but covertly seek to obtain better genes from other potential mates. They have a caring partner to establish safety, and they get good genes from extra-pair partners. Sounds like an evolutionary dream but a societal nightmare, right? Things are not that simple. This theory definitely does not apply to all women in all circumstances, and researchers are trying to figure out exactly when and how women employ this strategy.

Does the menstrual cycle secretly manipulate women?

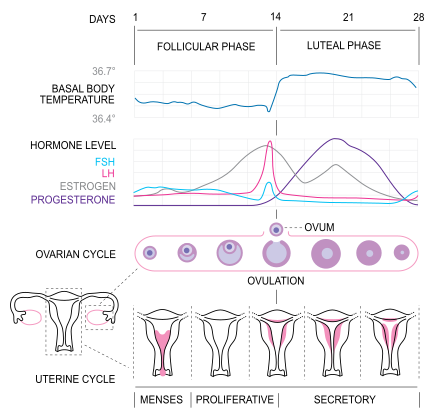

The menstrual cycle happens every month to prepare women’s bodies for a possible pregnancy. The whole cycle is coordinated by hormones, including estrogen and progesterone. During the follicular phase, an egg matures while the uterus walls thicken to prepare to host the fertilized egg soon. At the end of this phase, the egg is released from the ovary in a process called ovulation and directed toward the uterus through the fallopian tubes. If the egg meets a sperm during this process, it is implanted in the thick, comfy uterus. If no sperm was there to fertilize the egg, progesterone levels gradually fall and cause the uterus wall to crumble down. The inner lining of the not-so-comfy-anymore uterus and some blood are discarded from the body in the process called menstruation. A woman is most fertile during ovulation and in the 5-6 days before. Once released, the egg dies quickly in about 24 hours. But sperm can stay viable for a few days in the women’s system. That is why the fertile period is longer than just a day.

Pillsworth and colleagues hypothesized that women should be more into extra-pair mating during ovulation when the egg is waiting for a sperm with nice genes. They monitored women throughout their cycle and asked them to rate their partner’s attractiveness and their own desires towards the partner or extra-pair candidates1. It turned out that women who think their partners are low in sexual attractiveness display a higher interest in extra-pair sex during their high-fertility window compared to low-fertility periods. So, if the male partner lacks signals for nice genes, the dual-mating strategy is in play when the woman is ovulating. No increased tendency for extra-pair sex was observed for the women who reported having highly desirable partners. Moreover, when women were ovulating, their male partners were reported to show more love and affection, possibly a strategy evolved to prevent any extra-pair mating of the women.

In a later study, researchers took this to the next level2. They didn’t just rely on the reports of women on their partners’ sexual attractiveness. They asked independent judges to rate photographs of the male partners. These judges were a mix of males and females. This less biased study confirmed the former results. Women whose partners were rated as less attractive by independent judges had more extra-pair inclinations during their high-fertility period.

These extra-pair desires do not necessarily translate into a reduced commitment to the primary relationship. In fact, researchers found no change in women’s reported commitment levels in high fertility days3. However, women with less sexually desirable partners felt less close to their partners and were more critical of their faults during the fertile window. So, the women’s perspectives about the relationship shifted, but not their willingness to stay in that partnership.

The researchers also wondered if the overall sexual desire of women increases during ovulation4. This was the case only for mated women. No significant peak of sexual desire was found in women who were not in a relationship. Making offspring is good, but you also need to be able to take care of it after all. Having a partner increases your chances of doing so properly. Another interesting finding was this: women in longer relationships were more likely to feel extra-pair desire during their fertile window. If pregnancy with the partner does not occur for a long time, the body might start looking for other opportunities. Those genes are not going to transfer themselves! However, this also depends on the perceived quality of a relationship. Extra-pair desires were more likely for women who gave a lower quality rating to their relationship. Not entirely shocking. Looking for external mates can be incredibly costly, so if a woman has a good relationship already, it biologically doesn’t make any sense to waste her efforts on extra-pair matings.

What about what women wear on any given day? You guessed it, the menstrual cycle affects that too.

Scientists photographed 30 women throughout their menstrual cycle5. These photographs were later judged by 42 independent men and women. Judges were presented with a set of images belonging to the same woman and asked in which image the woman was trying to look more attractive. The images that the judges chose were mostly of women in their fertile window rather than low-fertility time points. Also, the closer a woman was to ovulation in that fertile window, the better the chance that the image was chosen. Women near ovulation tended to wear more fashionable clothes (according to the judges) and to show more upper body skin. It is known that the menstrual cycle results in subtle changes in body odors and facial expressions. But those things are kind of hidden signals. This study suggests that the cycle also leads to very overt behavioral changes. It makes perfect sense. The women would want to increase their mating chances, whether in-pair or extra-pair, near ovulation.

This research should not scare anyone.

I could have titled this post “Women are genetically programmed to cheat.” That is actually the title of an article about Pillsworth’s research in a major news outlet. But that would be incredibly misleading. Our ancient ancestors developed some adaptations with the drive to carry out their race. We still carry those adaptations even if we don’t need them anymore. However, that doesn’t mean that they rule our lives. We defy evolutionary adaptations all the time. One commits the biggest evolutionary sin by not having biological children and adopting instead. Still, actions like having a child or cheating on your partner are ultimately choices we have control over. Rather than using science as an excuse for questionable behavior, we should use it to be more mindful of all the factors affecting our decision-making and reflect more thoroughly before an act.

Resources

- Pillsworth, E. G., & Haselton, M. G. (2006). Male sexual attractiveness predicts differential ovulatory shifts in female extra-pair attraction and male mate retention. Evolution and human behavior, 27(4), 247-258.

- Larson, C. M., Pillsworth, E. G., & Haselton, M. G. (2012). Ovulatory shifts in women’s attractions to primary partners and other men: Further evidence of the importance of primary partner sexual attractiveness. PLoS one, 7(9), e44456.

- Larson, C. M., Haselton, M. G., Gildersleeve, K. A., & Pillsworth, E. G. (2013). Changes in women’s feelings about their romantic relationships across the ovulatory cycle. Hormones and Behavior, 63(1), 128-135.

- Pillsworth, E. G., Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2004). Ovulatory shifts in female sexual desire. Journal of sex research, 41(1), 55-65.

- Haselton, M. G., Mortezaie, M., Pillsworth, E. G., Bleske-Rechek, A., & Frederick, D. A. (2007). Ovulatory shifts in human female ornamentation: Near ovulation, women dress to impress. Hormones and behavior, 51(1), 40-45.