We humans are not on the best terms with aging and death. They are inevitable, but we choose to ignore this fact until we have to face them for real. As a scientist who wishes to ease the suffering in the world, I study the secrets of aging and how we can use this knowledge to our advantage. Not a complete prevention of aging per se; I think we all need to go through it and learn from it, but healthier aging is the goal. I won’t be writing about my own research today. We will now dive into “cognitive reserve” and how speaking multiple languages is a neat anti-(cognitive)aging trick.

One of the most life-quality-reducing aspects of aging is cognitive decline. This affects the abilities of memory, reasoning, planning, decision-making, sensory impairments, and many more. A severe form of cognitive decline is dementia. A 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) report estimated the global societal cost of dementia as US$ 1.3 trillion1. By 2030, it is expected to rise to US$ 2.8 trillion and exceed further. So, it’s well worth figuring out ways to slow or prevent disorders like dementia.

Can you escape dementia by learning languages?

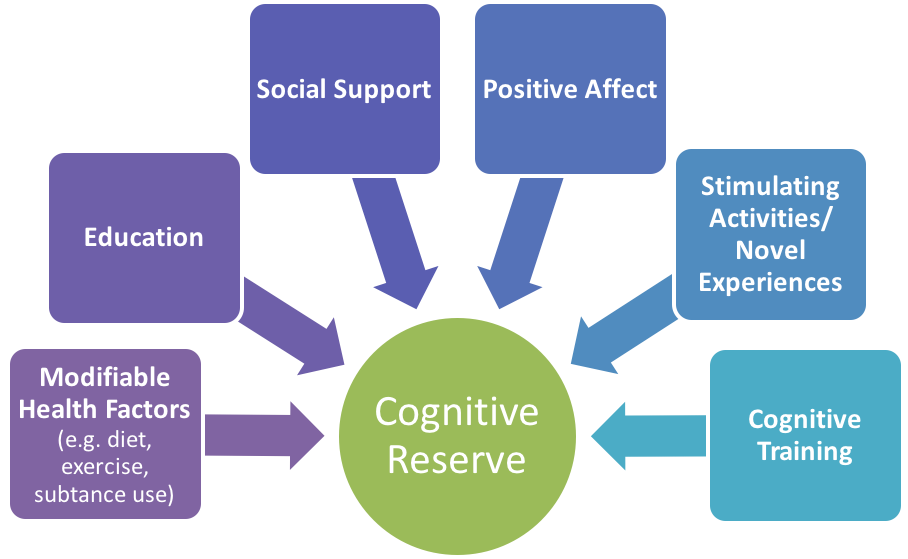

It is intuitive to think that if the brain structure is compromised, it would negatively affect cognitive abilities. Actually, that’s not always the case. This disparity between the brain structure and cognitive level is called cognitive reserve (CR). Many things can affect CR, including lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise, formal education, social support, a positive outlook on life, stimulating activities and employment, and novel experiences2.

Another fascinating factor is multilingualism. While a substantive amount of research is on bilingualism, there is evidence that speaking more than 2 languages further strengthens the cognitive reserve3. Bilingualism is associated with better cognitive function in older people than it would be predicted from their brain structure. It also delays the appearance of dementia-related symptoms by 4-5 years4.

How does being bilingual keep our brains active and kicking?

I’m currently learning Dutch because I call the Netherlands my home now. I already use Turkish and English all the time. Now, with the third language in daily use, my brain is just a mosh pit full of jelly. I realize that I have very little control over switching them on and off. I can’t control the switch. What the research says is: There is no switch! The minds of bilinguals and multilinguals are constantly busy settling the competition between different languages5. There is no on-off switch. These people are better cognitive negotiators and problem solvers. Therefore, they are more resistant to cognitive function loss caused by aging brain structure. Studies also found increased connectivity between brain cells in the brain’s executive control network in bilingual individuals.6

Eventually, even for language freaks, brain pathology accumulates, and the tipping point is passed, leading to fast cognitive decline. Still, people with high cognitive reserve experience this later when they have more advanced damage. They are functional for more of their life. Usually, when bilinguals get their diagnosis of dementia, they are at a more advanced stage. At first glance, it may seem like being bilingual makes them sicker. But actually, they get caught at a later level because they start presenting symptoms much later, thanks to their cognitive reserve7.

There have been studies finding no or minimal effect of bilingualism on cognitive function. However, meta-analyses compiling and analyzing dozens of studies report in favor of bilingualism. A recent such analysis concluded that being bilingual does not prevent the occurrence of the disease. Still, it significantly delays the time symptoms start manifesting8. You wouldn’t say no to 5 more years of well-functioning brain activity.

How many languages do we need to keep dementia at bay?

With my native Turkish, high-level English, up-and-coming Dutch, so-so Spanish, and fading Russian, I feel like my brain cannot take in any more. Although I reeeally want to get that Russian thing going again one day. Anyways, does each additional language make your brain even stronger? Scientists say: Hell yeah! A study monitored over 200 participants aged 65 who were non-demented. People who practiced more than 2 languages appeared to have a lower risk of cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND). The most striking part is that advancing from 2 to 3 languages increased the protection from CIND a whopping 7-fold3.

Which age is the best to start learning languages?

Bilingualism’s positive cognitive impacts can be detected as early as 2 to 6 years old. A study even found that 7-month-old children raised in bilingual homes were better at adjusting their responses if the rules of the situation changed compared to children who live in monolingual homes9. Another study compared kindergarten children who are raised natively bilingual with children in an immersion program to learn a second language10. Native bilingual children outperformed their peers on cognitive tests. This underlines the importance of consistent early exposure to two languages. As for the oldies, even though learning a new language in old age might be more challenging, studies suggest an overall benefit on cognitive performance and other outcomes such as self-esteem11.

So, now go download that language app again.

Whether language learning can be used therapeutically for older people is still yet to be explored. But until effective pharmacological therapies are developed to interrupt aging, our best shot is lifestyle interventions. We should focus our attention on experiences that boost cognitive reserve, such as exercising, being open to out-of-the-box experiences, creating a solid social support network, and of course, learning and regularly using new languages. Maybe now you are inclined to give your old rusty French a polish.

Sources

- WHO. “Dementia” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20the%20estimated%20total,dementia%20and%20care%20costs%20increase.

- Bialystok, Ellen. “Bilingualism: Pathway to Cognitive Reserve.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences (2021).

- Perquin, Magali, et al. “Lifelong exposure to multilingualism: new evidence to support cognitive reserve hypothesis.” PloS one 8.4 (2013): e62030.

- Craik, Fergus IM, Ellen Bialystok, and Morris Freedman. “Delaying the onset of Alzheimer disease: Bilingualism as a form of cognitive reserve.” Neurology 75.19 (2010): 1726-1729.

- Kroll, Judith F., Susan C. Bobb, and Noriko Hoshino. “Two languages in mind: Bilingualism as a tool to investigate language, cognition, and the brain.” Current directions in psychological science 23.3 (2014): 159-163.

- Perani, Daniela, et al. “The impact of bilingualism on brain reserve and metabolic connectivity in Alzheimer’s dementia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114.7 (2017): 1690-1695.

- Stern, Yaakov. “Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease.” The Lancet Neurology 11.11 (2012): 1006-1012.

- Anderson, John AE, Kornelia Hawrylewicz, and John G. Grundy. “Does bilingualism protect against dementia? A meta-analysis.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 27 (2020): 952-965.

- Kovács, Ágnes Melinda, and Jacques Mehler. “Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106.16 (2009): 6556-6560.

- Carlson, Stephanie M., and Andrew N. Meltzoff. “Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children.” Developmental science 11.2 (2008): 282-298.

- Klimova, Blanka. “Learning a foreign language: A review on recent findings about its effect on the enhancement of cognitive functions among healthy older individuals.” Frontiers in human neuroscience 12 (2018): 305.